Finished in October 2019

Dust Clouds and Debris - The Tragic Legacy of Minoru Yamasaki

By Zac Langridge

|

Remnants of a legacy; the tridents of the Twin Towers.

|

When an architect goes forward to design and construct a building, it’s safe to assume that they’d like their legacy to live on through such buildings. I’m no architect myself, but if I was, I’d love my creations to remain on the face of the earth for centuries. I’d love my buildings to make an imprint on people’s lives, garner wide praise, and be known for nothing but what they were: pieces of architecture.

It’s safe to say that Minoru Yamasaki would’ve liked this as well.

Tragically, his legacy was warped into something quite different.

An American architect of Japanese descent, Minoru Yamasaki is famous for his buildings being destroyed. His Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St. Louis was demolished less than twenty years after its initial construction, and his famous World Trade Center in New York was the target of the largest terrorist attack in history.

When one thinks of Minoru Yamasaki - or at least his buildings - it all ends at a horribly bleak dead-end. Imagery of crumbling concrete, twisted steel and huge billowing clouds of dust will probably be flashing across people’s minds. Collapsing high-rises and piles of shattered debris are the themes that tend to interlink the two most famous projects of his career. Accompanying both project’s demises, like a blood-red cherry on top, is the cost of innocent human lives - something that the architect clearly didn’t intend or anticipate. It’s sad.

One of the most intriguing things about this man, is how he’s one of the most overlooked architects of modern times. Many people know his buildings, but they don’t know about the man behind them, or don’t care. For many bystanders, the Twin Towers appear to have never had an architect; they were just constructed by nameless, faceless individuals with tools and plans conjured up out of nowhere, just like how regular buildings appear to be built. But Pruitt-Igoe and (especially) the Trade Center were never just

regular buildings, so it intrigues me as to why so many people haven’t heard of the man who created them.

And many of those who

had heard of Yamasaki, apparently never really understood him or his work from the get-go. Although he was one of the most famous Asian architects of his time, the community of which he was a part of appeared to consider him somewhat of an outsider, and the critics generally showed a level of disdain towards his persona, his buildings, and the styles of architecture which he ingrained in his works (‘modernism’ and ‘new formalism’). Despite having garnered acclaim and admiration during the earlier decades of his career, his success was followed by a slow decline which eventually culminated in the 9/11 terrorist attacks, cementing Yamasaki’s place in history as an “

architect of disaster”. These days, if anyone does decide to flit briefly over his history, the destruction of his two most infamous works would only further dirty the perception that a regular (uninformed) person would have of him.

“So the Twin Towers weren’t the only well-known buildings of his to be destroyed? Hmph. He must’ve been terrible at his job!” Here, I’m going to shed some light on the injustices of Minoru Yamasaki’s history and legacy, recounting both the construction and destruction of his two most high-profile works. Hopefully from this, I will be able to walk readers out of the dust clouds unscathed, and help them understand the man behind two of the most catastrophic failures in building history.

Pruitt-Igoe (1954-1972)

|

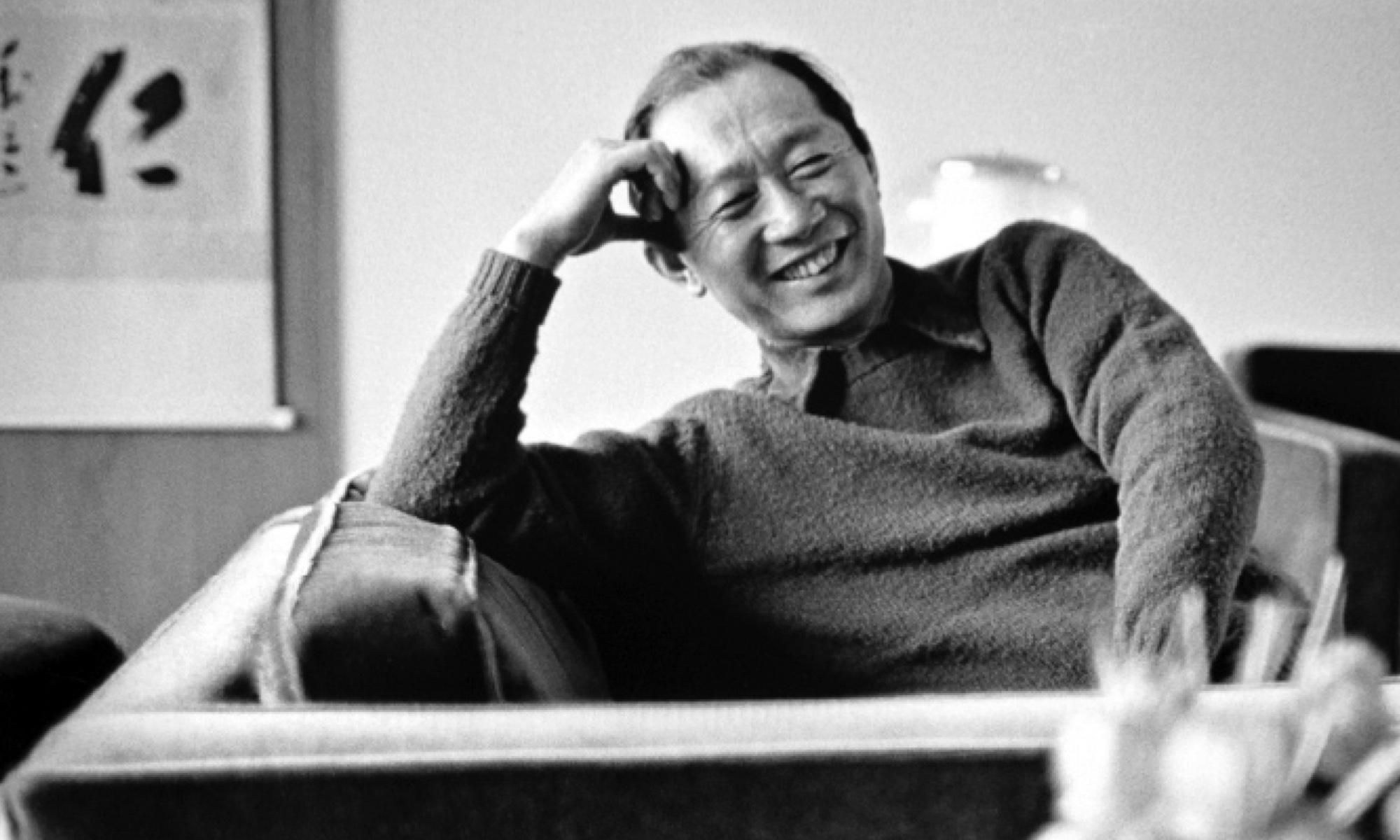

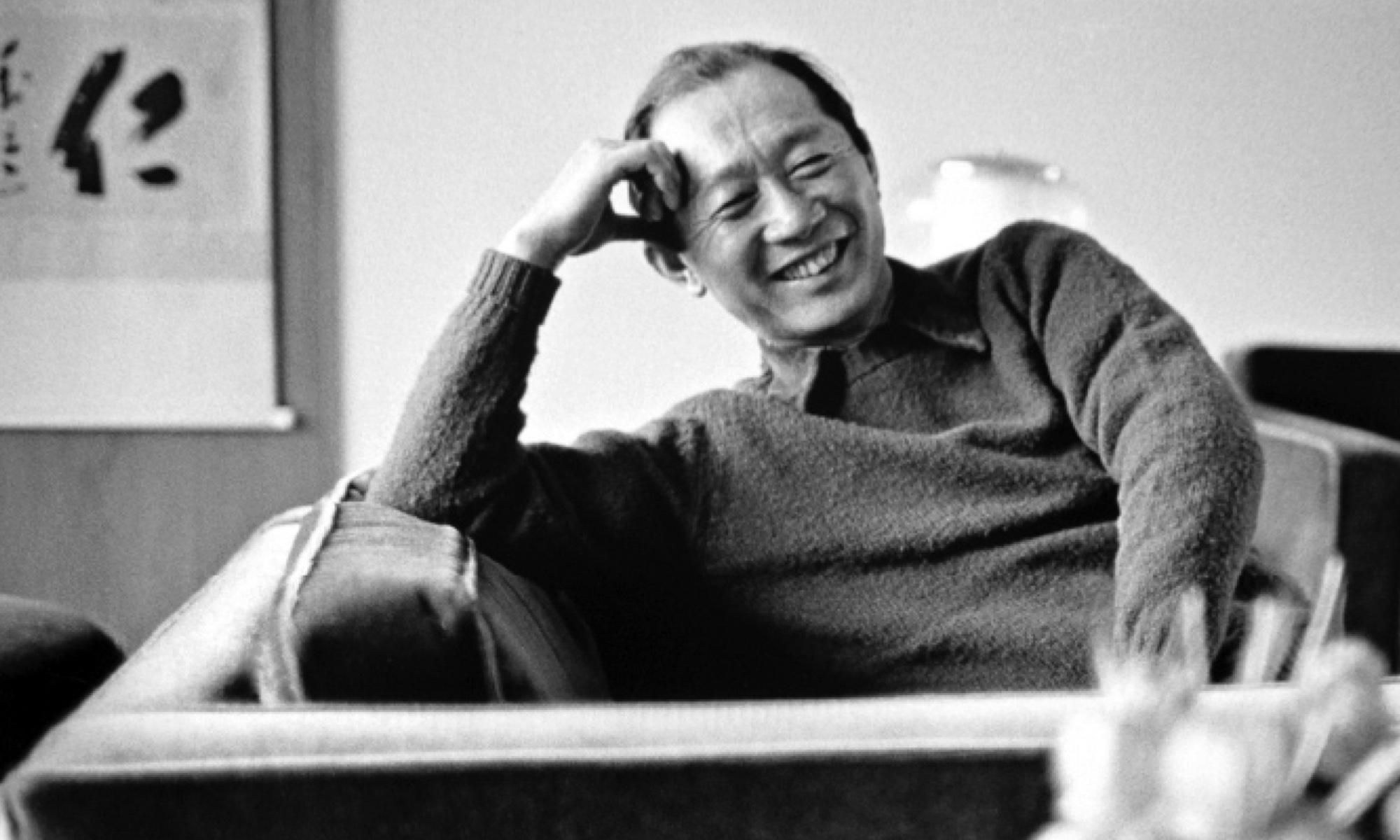

| Minoru Yamasaki (1st of December, 1913 - 6th of February, 1986). |

Minoru Yamasaki was born in Seattle on the 1st of December, 1912. A second-generation immigrant from Japan, he was inspired by his uncle to become an architect, and enrolled at the University of Washington when he was sixteen. Once he’d graduated in 1934, he moved to New York and, after completing a master’s degree in architecture, he found work with multiple firms which had designed many famous buildings around the city. Most notably, the architectural firm of Steve, Lamb and Harmon, which had designed the tallest building in the world at the time - the Empire State Building. It seems as though in hindsight, that Yamasaki’s future was destined to revolve around tall, multi-storied buildings.

However, in reality, Yamasaki started off designing much smaller projects in 1949, following the creation of his own firm with colleagues Joseph Leinweber and George Hellmuth. The three would construct buildings locally, and the firm became successful enough that Yamasaki and his buildings began to draw attention. As a result of this, the next two decades would be one of success and praise for the architect. This largely stemmed from his ambitious designs which revolved around the popular architectural style of the time, modernism, and fusing it with touches of gothic flair, as well as incorporating styles from his ancestral country of Japan. The results were unique, sleek buildings that were minimalistic and often incorporated straight lines and symmetry. This would contribute to the birth of a new style known as ‘new formalism’, which Yamasaki became a practitioner of. While this success would lead to an award in 1956, and his face being featured on the cover of Time magazine in 1963, it all was kicked off in 1950, when the attention garnered by Yamasaki’s local constructions led to him being hired for assisting urban renewal development in St. Louis.

|

Yamasaki was, at nature, an architect of elegance, as seen here in a

model of his planned Oberlin Conservatory of Music. |

With the vast population of white middle-class Americans moving out of the vast, cramped grids of the cities to the spacious, peaceful and desirable suburbs, the urban environment became run down and poorly maintained. With much of the remaining urban population being poorer, less privileged black citizens, the mayor of St. Louis, Joseph Darst made the decision to construct cheap high-rise housing in order to provide homes for such citizens, as well as to help draw people back to the city. Enter Pruitt-Igoe. Yamasaki’s major career kickstarter came when Darst hired him and his firm to helm the design and construction of the planned high-rise housing. It would be merely the first project in a massive grand plan to effectively replace the slum districts of the city with tower blocks.

The DeSotto Carr slum was leveled, and Yamasaki, incorporating his trademark modernist style into the designs, came up with a neighbourhood of thirty-three concrete apartment blocks. The buildings were clean-cut, symmetrical, and brutalist. Each had a single road leading past it’s front, plus car parks, perfectly manicured lawns and paths leading to front doors. Playgrounds were placed below the apartments for children to play. The complex contained 2,870 housing units containing space for over 15,000 residents. Still, It was effectively mass-produced as a haven for community; the modernist designs resulted in “rivers of green” to provide natural relief in the concrete surroundings, large and sunlit windows, and galleries giving access to the units which would allow residents to interact in vibrant, friendly environments. Although it was designed for both black and white residents, almost all of the complex was occupied by the former, many of whom moved from the slums (including the one demolished for the project - ironically not the only old neighbourhood which would be destroyed to accommodate a building of Yamasaki’s). The reception towards Pruitt-Igoe was overwhelmingly positive in its first years, especially from the residents, one of whom recalled that “the day I moved in was the most exciting of my life”. However the architectural and political community, as well as urban developers, too praised Yamasaki’s creation, believing it to be a clear solution for urban renewal and housing crisis in America. High-rises as substitute for houses was affordable and easy.

|

Shock of the new! - the ill-fated Pruitt-Igoe housing complex dominated

the surrounding slums it was supposed to replace. |

There were, however, problems from the get-go. Yamasaki and his firm were largely restricted by the budget provided, and the dimensions of the site itself. They initially proposed a complex full of high, mid and low-rise buildings, but the St. Louis Housing Authority forced them to go through with the design that ended up becoming reality. Budgetary concerns were the motive for this. To push the budgetary concerns even further, the materials provided to the firm to construct the complex was often lacking, and of poor quality. The number of facilities needed to keep the place in adequate condition for residents, such as toilets and playgrounds, was cut down dramatically. Lifts only stopped at every third floor. And crucially, the complex was segregated after being initially split into two sectors (the black residents were intended to live in the Pruitt apartments, while white residents would reside in the Igoe buildings), leading to many fleeing and living elsewhere. Those who remained were poorer families with nowhere else to go.

It seemed Pruitt-Igoe had been set up to fail from the beginning of its construction. And fail it did. Spectacularly. The first major signs of trouble began when the occupancy rate in 1957 (91%) began to decline in the following years. I’d assume this was due to the poor living conditions inside caused by the flimsy materials the complex was composed of. The towers’ maintenance would be “supported by the tenants rents”, but due to many of the residents being so poor, there was little funding to keep the place in pristine condition. The thirty-three apartments would often fall into disrepair, driving many occupants out and ballooning vacancy rates rapidly. As a result, less money was available to repair the buildings, which led them to fall into further disrepair, which in turn drove out more residents, which resulted in less money to fund repairs, which led to the buildings becoming further derelict, and so on…. The cycle would continue until it destroyed the project from the inside out. The buildings started to decay and rot; their lifts became tattered, lights stopped working, windows were smashed, graffiti started to appear, etc. The apartments’ plumbing and heating pipes often burst, and in one winter, spurting water from said-pipes froze entirely, forming spears of ice that hung from window ledges. Residents lived in cold and discomfort, and as their numbers became sparse, crime started to take its place. The hollowed out spaces in the apartments became areas for criminals and gangs (some of whom didn’t even live in the complex) to thrive. Residents lived in fear of being mugged, raped, or even killed. Innocent lives were lost. Many citizens of surrounding St. Louis refused to go near the complex, and wouldn’t even approach the roads that entered the hostile, decaying environment. What had started off as a utopia for those living in the slums, and a new solution for St. Louis’ declining inner-city population, had deteriorated into a hell on Earth, and was (in the words of Dr. Lee Rainwater) “an embarrassment to all concerned”.

|

Yamasaki's housing project became a prime example of urban decay at its

ugliest. |

I personally believe that the failure of the Pruitt-Igoe experiment was hardly the fault of its architect. Minoru Yamasaki had been given limited resources to construct the facilities, and had been given many restrictions by the St. Louis Housing Authority in order to cut costs. The local government had believed that constructing high-rises to house mass-populations would be a simple solution to draw Americans back to the cities, but hadn’t addressed the issues driven by racial inequalities, and the resulting lack of funding and maintenance that plagued the project from the get-go. The economy, industries and population of St. Louis had all been in decline during the ‘50s, and Pruitt-Igoe was designed to halt that decline. It didn’t work, and the reasons for that can hardly be blamed on Yamasaki. All the same, Pruitt-Igoe had become a disaster, and something had to give. After almost two decades of decay, the occupancy rate had shrunk to only six-hundred residents in 1971. Finally, in the following year, the Housing Authority and local government made the decision to reduce the size of the complex. Half a building was demolished with high-explosives on the 16th of March, 1972, and on the 21st of April, a second building was demolished. This second controlled demolition was photographed and recorded by the media, photographers and filmmakers, and was broadcast across the country. The soon-to-be-famous footage shows the foundations of the structure being blasted out from underneath it, and the eleven-story concrete building sags into a rising cloud of its own dust, its fragmentation hidden almost entirely from view.

The eerie images appeared to send ripples of discussion across the world, and became a symbol for what would be proclaimed as the “death of modernism”. The ideals and purposes of modernist architecture was to draw the line on “form follows function”. Modernist structures weren’t supposed to look nice or call attention to themselves, but were supposed to serve the occupants with a purpose that would border on almost cold, authoritarian precision. Modernists built “machines for the living”, according to architect Le Corbusier, and such machines wouldn’t indulge in such pleasures as privacy or large, unnecessary amounts of personal space or flair. However, by the time the 1970s rolled around, the indistinguishable tower-blocks aligned neatly in rows without any clear individuality appeared stifling and intimidating. The endless rows of windows, unrelenting concrete walls, and identical living units stacked atop one another now seemed harsh, controlling and alien - a symbol of communism. The modernist movement, which had been acclaimed decades before, was now the victim of ruthless attacks and malicious panning from architectural critics. Oscar Newman stated in his work

Defensible Space: “Because all the grounds (of Pruitt-Igoe) were common and disassociated from the units, residents could not identify with them (….) Corridors shared by 20 families, and lobbies, elevators, and stairs shared by 150 families were a disaster—they evoked no feelings of identity or control. Such anonymous public spaces made it impossible for even neighboring residents to develop an accord about acceptable behavior in these areas. It was impossible to feel or exert proprietary feelings, impossible to tell resident from intruder.”

|

The much-photographed destruction of Yamasaki's high-rise complex on

the 21st of April, 1972. Eerily, it wouldn't be the last of his

work to suffer such a fate. |

The result of this was a wave of scathing attention towards Pruitt-Igoe, and in extension, Minoru Yamasaki. It appeared to many as though the failure of the housing project had everything to do with its design, and the apparent psychological behaviours it encouraged. Of course, it wasn’t until many years later when academic Katherine Bristol, and a documentary called

The Pruitt-Igoe Myth both tried to dissect the real causes behind the decay of the ill-fated project; that being the poor planning of such urban renewal, and the cost-cutting restrictions that only doomed it from day one. However at the time, the blame was all on Yamasaki and his apparently flawed designs for the utopia of the future. The failure and “death of modernism” was slathered all over his once prestigious reputation, and the remaining apartments of Pruitt-Igoe were torn down. For decades the area in which they once stood was untouched, becoming an overgrown block of forested land which concealed the cracked roads, dead street-lights, and piles of crushed concrete which were all that remained of Yamasaki’s modernist neighbourhood. It’s now apparently being redeveloped.

The rise, decline, and eventual destruction of his work apparently took a toll on Yamasaki. He’d basically became the poster-man for Pruitt-Igoe’s disastrous failure, and even started to believe that he was to blame. In his multiple reflections, he appeared to take responsibility for its decay. In a speech at the New York Architectural League, he

stated that he “lost sight of the total purpose, that of building a community (....) We have designed a housing project, not a community, which is tragically insensitive to the humanist aspects of security and serenity and have multiplied tragedy because of the great number of buildings and extent of site.” Several years of his life had been dedicated to Pruitt-Igoe and the urban renewal of St. Louis, and it had been his calling-card to architectural fame. Seeing it destroyed in such a tragic fashion must’ve been heartbreaking for him. “I am perfectly willing to admit that of the buildings we have been involved with over the years, I hate this one the most.” Even so, he still acknowledged that “if I had no economic or social limitations, I’d solve all my problems with one-story buildings”, and made it clear that the flawed final design wasn’t his original intent, but one forced upon him by compromises from higher up. His

final word on Pruitt-Igoe: “I never thought people were that destructive (....) I suppose we should have quit the job. It’s a job I wish I hadn’t done.”

World Trade Center (1973-2001)

|

The planning of an icon; Yamasaki observes the impact

of the WTC on a model of New York. |

Around the time Pruitt-Igoe was being vandalized and defaced, Yamasaki was hired for another project that would cement his name in architectural history.

The idea of an international world trade and finance center in New York City, initially shelved for a least a decade, was brought up by real-estate developer David Rockerfeller in 1959. Similarly to what Pruitt-Igoe was supposed to be for St. Louis, this new complex would be just part of a one billion dollar redevelopment plan for the southern tip of Manhattan. As much of the new urban activities of the time continued to flourish further north in Midtown Manhattan, where such iconic skyscrapers as the Flatiron, Chrysler and Empire State were located, the Financial District at the southern tip of the island was becoming old, dirty and somewhat run-down. Rockerfeller planned to revitalize Lower Manhattan, starting with the World Trade Center, which was at the time planned as a massive futuristic mart or shopping mall-type building.

By this point, Minoru Yamasaki had propelled his career to ever greater heights. Marching on from the completion of the ill-fated St. Louis housing project, he gained increasing fame and success with his terminals at the St. Louis and New York City airports, and was then chosen to design the US Consulate in Kobe, Japan. He was invited to build an airport in Saudi Arabia, and by the early ‘60s, he’d started designing a number of high-rise buildings. Much of his architecture was praised for being sleek and modernist, while simultaneously incorporating traditional flourishes from architectural styles around the world. A famous example of this would be the Pacific Science Center he designed in Seattle; the building surrounds a plaza accompanied by reflecting pools (reminiscent of Japanese gardens) and accompanied by towering white arches (a Gothic motif that Yamasaki would utilize throughout his career). It was clear that he was becoming one of America’s most trendy architects, with his unique and innovative style that tried to humanize even the most sleek and alien of structures.

|

| 1963's trendiest contemporary architect. |

In 1962, he was hired by Rockerfeller and the Port Authority of New York, to construct the World Trade Center. Over the next few years, he and his colleagues, plus the Port Authority and much of New York’s local government, would go through multiple designs and ideas in order to figure out the layout, scale and aesthetics of the enormous complex. Located on the western side of the island and near the Hudson River, the planned site would occupy sixteen acres. As a result of this, the architect would eventually settle on a two-towered (or “twin-towered”) design, accompanied by a vast plaza on ground-level - a place for the citizens to socialize and interact with the surrounding city environment, before entering office workspace. Once again staying true to his ideals of humanizing artificial environments, he apparently drew inspiration from the Piazza San Marco plaza in Venice for this, making areas for trees to be planted and sculptures to liven up the courtyard. His two towers, he proclaimed, would be 80 stories tall.

The Port Authority approved the design, but mandated Yamasaki to make a key change. The towers would have to be taller. Due to the incredible demands of the Trade Center (it was required that the complex have 10,000,000 square feet of office space) and the increasing ambition of the United States at the time, it was demanded that the twin skyscrapers’ height be upped to 110 stories each. That would make them the tallest buildings in the world. Yamasaki was initially concerned about this, as the amount of elevator shafts and stairwells needed to occupy a 110 story high-rise would completely fill up the interior of the tower, making offices cramped and undesirable. In order to overcome this obstacle, the designers would need to become innovative in order to engineer an economic elevator system for the two buildings. The budget ballooned, and the World Trade Center project was full steam ahead.

|

The North and South Towers rise, shockingly futuristic against

the stone of late 19th century architecture. |

However, not everyone was enthusiastic about the arrival of the new complex. The planned sixteen acres where the complex would sit, was occupied by a small neighbourhood known as Radio Row. This area was home to New York’s electronics industry, and was occupied by many businesses and around a hundred-or-so tenants whose livelihoods depended upon the workspaces there. Understandably, they were heavily opposed to the World Trade Center project, which required not just their eviction, but the demolition of their entire neighbourhood in order to make space for the massive buildings planned. Locals were vocal about their displeasure, staging protests and even seeking legal action. Urban planners and other architects heavily criticized the planned project too. Many

saw the Twin Towers as an example of the Port Authority merely trying to “enrich itself at the expense of the entire city”. Lawyer Theodore Keel’s words on the matter: “A striking example of socialism at its worst”. However the complaints and lawsuits were tossed aside, and the residents were uprooted from their homes. Then arrived the men and machinery, and by the might of the wrecking ball, Radio Row’s 164 old buildings and streets vanished from the face of New York. The void where the charming little village used to be, would be entirely filled by an immense complex of five huge buildings, including Yamasaki’s two Trade Towers. Construction on 1 WTC (the North Tower) began in August of 1968, while work on 2 WTC (the South Tower) began in January of the following year.

Preceding and during this construction, Yamasaki and his colleagues addressed the issues with the elevator system, as well as the speed in which the towers would be built. Rather than treat each tower like a singular tall building, Yamasaki designed the structures as if they were each composed of three forty story buildings stacked on top of another. At the intervals between these three buildings would be “sky lobbies”, places where occupants could leave a main (“express”) lift and take another secondary lift to a higher floor if need be, therefore eliminating the need for dozens of extra lifts needed to service the flood of thousands of tenants entering and exiting the building. Another innovative design would speed up the construction of the towers: the creation of the “tube structure”. Past skyscrapers had been built out of massive steel frames, enormous interlocking grids of metal beams that stretch thousands of feet into the air. The construction of such a structure is long and expensive, and to save time and money, Yamasaki and fellow engineer Leslie Robertson came up with the “tube” design. Instead of interlinking the support columns throughout the building, they would be aligned along the perimeter walls in a tight mesh, like a square mosquito net of steel that surrounded the building’s core. The steel exterior beams would be assembled into prefabricated sections, delivered to the site, hoisted up by cranes, and ultimately riveted into place. These wouldn’t be the only innovative engineering feats achieved during the construction of the Trade Center (see the famous “Bathtub”), but they’re certainly two that Yamasaki contributed heavily to.

|

"Scaled to man" was how Yamasaki felt architecture should be, yet

many saw his World Trade Center as contradictory to his

own self-proclaimed ideals. |

Throughout the design and construction of the World Trade Center, Minoru Yamasaki would try his best to humanize and harmonize the brutality of the vast complex. It was very clear that the Twin Towers would be enormous, constantly dominating the Lower Manhattan skyline and overwhelming much of the surrounding neighbourhoods and streets. Once again, the architect would be applying his style of new formalism to the towers - clean lines and symmetry, with little unnecessary flourishes - however even so, he still made attempts to bring his own personality to the towers. At the base of the buildings, the perimeter columns traveling down the sides would split apart into three, forming arches or ‘tridents’ - a touch of his trademark Gothic inspirations. Steel trees sprouting from the plaza and climbing 110 stories into the sky. Also to reflect his own ironic fear of heights, Yamasaki designed the windows of the towers to be about the width of a person’s shoulders, leaving small slits of glass bordered by two thick columns of steel. As a result, the Twin Towers appeared to be entirely windowless from a distance, and inside the occupants would feel safe and secure. Vertigo wouldn’t be a problem. Once again, these small touches appeared to be gifting the buildings to the humans that would use them. Unlike the case of Pruitt-Igoe, Yamasaki was here allowed to grant the occupants of his buildings the humane touches he felt it needed. In 1962, he stated: “Architecture must be dignified and elegant. It must be humanly scaled to man so that it belongs to him, so that he has pride in it, so that he loves it, so that he wishes to touch it.” It seems like an ironic statement, considering that this was coming from an architect used to designing small-to-medium sized projects for humanitarian purposes, and yet here were two 110 story skyscrapers that completely dwarfed everything around them. Despite his humanist touches, Yamasaki’s towers were certainly not “scaled to man”, and instead loomed imposingly over the streets of New York, blocking out natural sunlight and creating strong wind vortexes that would cause no end of trouble for locals. Almost a decade following his previous statement, the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers were completed. The North Tower was completed in 1970, and the South Tower in the following year. Five more smaller buildings would eventually follow suit, however they wouldn’t be designed or built by Yamasaki.

By this time however, Pruitt-Igoe had fallen, and Yamasaki’s public perception had taken a tremendous downfall. Along with his humiliation, the ideals of modernism and new formalism had been completely shamed by the architectural community, and the design of the World Trade Center (which had been lauded by critics in the early-to-mid ‘60s) was now

viewed with an almost highbrow disdain or mockery. Much of the dislike towards the project was unavoidable from the start. Many New Yorkers were still seething at the destruction of Radio Row, which had not only evicted tenants and wiped out historic buildings, but also completely altered the grid-like traffic flow of Lower Manhattan. The massive complex had wiped out several streets along with the buildings, creating a vast superblock - a concrete and steel jungle - that was hated by critics and locals alike. Lewis Mumford famously deemed it an “example of the purposeless giantism and technological exhibitionism that are now eviscerating the living tissue of every great city.” As if to add insult to injury, much of New York’s existing office spaces were actually largely vacant, and many didn’t see the point of creating literally acres of new offices when so many were already available throughout the city. Some would declare this a “mistaken social priority” on the part of the Port Authority. However Yamasaki’s designs also became a focal point of the hatred towards the complex. The obvious contradictions between his humanist ideology and the sheer enormity of the Trade Center was easily singled out as a point of criticism. Ada Huxtable, an apologist of the towers,

admitted that “in spite of their size, the towers emphasize an almost miniature module —feet 4 inches—and the close grid of their decorative facades has a delicacy that its architect, Minoru Yamasaki, chose deliberately.” Some critics compared the towers’ designs to “glass and metal filing cabinets”, while others made infamous remarks about how they resembled “the boxes that the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building came in”. Others were less creative, and simply panned the buildings without any sugar-coating spared. In the words of Wolf Eckardt: “These incredible giants just stand there, artless and dumb, without any relationship to anything, not even to each other.” But even though both the Twin Towers had eclipsed the Empire State as the tallest buildings in the world, they only held the title for a year; the completion of the Sears Tower in Chicago stole it away in 1973. And even as far as tall buildings went, the view from inside was remarkably disappointing. Huxtable remarked that the slit windows were “so narrow, that one of the miraculous benefits of the tall building, the panoramic view out, is destroyed. No amount of head‐dodging from column to column can put that fragmented view together. It is pure visual frustration.”

|

The once-derided, now sorely-missed "filing cabinets" of

New York City. |

The World Trade Center has been re-evaluated over the years, especially since the 9/11 terrorist attacks, and is beloved and admired by many (myself included). But back in the early ‘70s, it’s safe to say that it failed miserably to win over the hearts of architectural critics and New Yorkers alike. The complex represented an overly ambitious Port Authority, that had not only destroyed a beloved neighbourhood, but had fallen spectacularly out of touch with the times of architecture and economic needs. Both of the towers would remain largely empty during their first years, leading both the Port Authority and State of New York to fill up much of the unoccupied floors with their own offices. It was surely an embarrassment for them. Adding to that, the Twin Towers were seen by many as an eyesore. Awkwardly jutting out of the middle of the worn-down financial district of Manhattan, the two skyscrapers’ severe grey facades and clean-cut lines appeared totally out of place when surrounded by the aged, art-deco stone buildings of the previous decades. The futuristic ambition of the ‘60s had become apparent by the early ‘70s, and had aged badly. The buildings remained either unloved or dismissed by many locals, but around the world however, the twin structures became icons of New York alongside the Statue of Liberty, Empire State Building and the Brooklyn Bridge. As well as that, they became instantly recognizable symbols of America’s economic prosperity and engineering marvels. The observation deck atop the roof of the South Tower became a go-to spot for tourists and visitors alike, and the “Windows on the World” restaurant in the North Tower provided diners with food, wine, and a stunning view. Eventually the World Trade Center did gather more tenants, which helped encourage the anticipated renewal and modernization of Lower Manhattan. Battery Park City was constructed just across the street from the complex, built on a landfill of earth that had been excavated during the construction of the Trade Center. This and the construction of the World Financial Center in the ‘80s helped absorb the initial impact of the Twin Towers on the skyline, softening their much criticized brutality. A terrorist attack by Islamic extremists occured in 1993, killing six, but failed to destroy the complex. Following this, New Yorkers appeared to finally accept Minoru Yamasaki’s World Trade Center as a part of their city.

9/11, Reflection, and Conclusion

|

| Calm before the storm; September 10th, 2001. |

The immense tube structure of the World Trade Center managed to absorb the impact of the terrorist bombing on February the 26th, 1993. But on September the 11th, 2001, Islamic extremists finally found a way to penetrate the towers’ steel defenses. Skyscrapers had been hit by planes prior to 9/11. The Empire State Building had been struck by a bomber on a foggy day in 1945. Yamasaki and his team had designed the buildings to withstand “multiple impacts from jet-liners”

according to project manager Frank DeMartini, but they couldn’t have foreseen the events that would take place on that day. No high-rise had ever before experienced a precise, deliberate assault by a modern jumbo-jet at top speed. Neither had any high-rise before experienced a fire created by almost ten-thousand gallons of ignited jet fuel. To make matters even worse, the hollow “tube” design of the towers “allowed the jet fuel to penetrate far inside the towers”, reaching the crucial inner core columns and setting office contents near the perimeters of the structures alight. If traditional steel frames had been used, the planes and fires may not have damaged the buildings as severely, and most of the debris and jet fuel would have remained in more contained spots. This didn’t happen. The North Tower was struck by Flight 11 at 8:46 AM, and withstood the damage and fire for one-hundred-and-two minutes. Flight 175 impacted the South Tower at 9:03 AM, which lasted for only fifty-six minutes in comparison.

2,606 people died in New York overall, including those inside the hijacked airliners, although it’s generally unknown just how many died inside the towers compared to those who died around or underneath them on the day. Due to the attack being completely unprecedented, the North Tower had the most recorded casualties, considering it was the first target. 1,402 people died in the building, most of them above the point of impact where the stairwells had been taken out, and fire and smoke (especially the latter) began to climb up towards them. An estimated 200 people either jumped or fell to their deaths. Others below the impact point were trapped in their offices by fallen debris or jammed doors that had been knocked out of place by Flight 11’s impact. Some others who weren’t trapped still wouldn’t make it out alive, as many elderly, obsese, or citizens with health conditions would struggle to descend the stairwells. The level of casualties in the South Tower was far lower, with 614 people reported to have been killed around or in the building. This can be attributed to the fact that many in their offices could see what had happened to the neighboring tower, and had already decided to evacuate by the time Flight 175 had arrived to strike the building. Most of the casualties were at the point of impact, as tragically the Port Authority had advised the tenants to stay at their desks until about 9:00 AM, when an evacuation was finally announced. The plane struck the building about three minutes later; directly at the point of impact was the 78th floor and its “sky lobby”, which was packed with around 200 people trying to access the lifts. Only fourteen to eighteen people managed to locate the single stairwell that had survived the impact, and were able to escape the tower before its demise. When the building collapsed, all its remaining occupants were killed. Despite it’s higher level of casualties however, sixteen people managed to miraculously survive the collapse of the North Tower.

However, to this day, 9/11 is still claiming lives. Even after the final aircraft crashed, and the final survivors were pulled from the rubble, a huge number of people started developing sicknesses and diseases in the years and decade that followed. Much of this was down to the immense cloud of materials released into the air by the collapse of the World Trade Towers, and the fires that continued to burn at Ground Zero for months after the day itself.

According to Dr. Micheal Crane: “...It had all kinds of god-awful things in it. Burning jet fuel. Plastics, metal, fiberglass, asbestos. It was thick, terrible stuff. A witch’s brew.” Among much of the composition of the cloud, was the cancer-causing material known as asbestos, which was apparently rife throughout the Twin Towers. Around the late ‘60s, when the towers were built, asbestos was added to fireproofing in various buildings, in order to insulate the steel beams and protect the materials. It was banned in the mid ‘80s, but by then, the floor trusses of Yamasaki’s towers had been sprayed with asbestos at least up to their 64th floors. As a result, the absence of this material at the impact zones left the steel girders exposed to the aviation fueled fires, and when the buildings did eventually collapse from top to bottom as a result, it was the aforementioned presence of this material lower down in the buildings, that helped contribute to the endless stream of innocent people developing diseases and illnesses. The dust that coated New York was inhaled by uncountable numbers of citizens. Among these included the rescue workers who worked tirelessly to clear debris, extinguish fires and search for survivors buried underneath the wreckage. 10,000 New Yorkers who’ve been diagnosed with cancer, have apparently had it linked to 9/11. By September 2018, it was

reported that 9,375 members of the World Trade Center Health Association were suffering from cancers of some type. 420 members had already died before this statistic was made public. It’s uncertain whether Minoru Yamasaki had any say in what went into the fireproofing in the Trade Center, as it was common practice in those times to use it in building construction. Even so, previous high-rise buildings had their beams insulated with concrete, a reportedly far more expensive solution. Maybe the Port Authority of New York mandated Yamasaki to go for the cheaper option this time around too, just like the St. Louis Housing Authority did with Pruitt-Igoe. Maybe the architect gave the green light to spray the steel with asbestos himself. Or maybe it was entirely out of his control. Either way, the composition of his buildings is having a lasting and catastrophic effect on New Yorkers over a decade after the towers fell.

|

Dust clouds engulf Lower Manhattan following the collapse of the

North Tower. |

Yamasaki himself never had to endure the terrorist attack of 1993, nor the final attack in 2001 which brought the towers down. Despite the construction of the World Trade Center being a monumental task that should’ve hailed him as a visionary and legend within the architectural community, Yamasaki ended up falling out of the limelight. Being known as the man who both “killed modern architecture” and “ruined the New York skyline” ended up tarnishing his reputation and legacy for a while. He apparently became very “self-critical”, and the remainder of his projects were no longer acclaimed or publicized. The majority of his constructions after the Trade Center, were of smaller high-rises in various cities around the US. Much of these buildings’ designs were “less experimental, less challenging, and often less visually interesting”. Some of his trademarks were still present, but many of these buildings were unremarkable rectangles, lacking much of the historical communal flourishes that he was once known for - perhaps a result of the criticisms he’d been previously receiving. It seemed as though his flair for buildings that served the occupants had been stifled by the pain of Pruitt-Igoe, and snuffed out by the enormity of the World Trade Center. His painful reflection on the former: “In spite of my vision for how architecture could genuinely improve the lives of people it seems that certain real social and economic conditions make this impossible.” And as if in a cruel irony, his words on the meaning behind the Twin Towers: “World trade means world peace, and consequently the World Trade Center is a living symbol of man's dedication to world peace (....) a representation of man's belief in humanity, his need for individual dignity, his beliefs in the cooperation of men, and through cooperation, his ability to find greatness.”

After reportedly years of physical ills and “increasingly heavy drinking”, Minoru Yamasaki died of stomach cancer in 1986.

|

Yamasaki died with regret for Pruitt-Igoe, becoming heavily critical of his work,

which was largely scorned by the architectural community. His legacy

would only be truly examined and honored years later. |

It’s safe to say that Yamasaki’s legacy was tainted by the September 11th attacks, irreversibly so to some degree. Although the aircraft hitting the towers in such a precise manner (and with such a malicious intent behind their controls) was something certainly out of his hindsight, the catastrophic failure of the buildings that resulted in hundreds-to-thousands of deaths, not to mention the everlasting health impacts on New Yorkers even today, is something that many onlookers could (and probably do) partly hold him responsible for. The failure of Pruitt-Igoe doesn’t help in the slightest. The negative attention that Yamasaki attracted in the past decades paints a sad picture of an architect who simply designed his buildings along the ideals he encompassed, but it only led to chaos and catastrophe, even after his death. However when doing further research, particularly into that of Pruitt-Igoe, it becomes apparent that Yamasaki was in many ways a scapegoat for the failures of others around and above him. As mentioned before, the St. Louis Housing Authority made many restrictions to his plans for the project, and his original ideas were scrapped to cut costs. In doing so, the government and housing authorities failed to comprehend the requirements of an apartment complex, as well as overlook the needs of its residents. Yamasaki also never intended the World Trade Center towers to be on the overwhelming, unfathomable scale that they were; it was the Port Authority among others who lobbied for the towers’ height to be increased from 80 stories to 110.

But even when you put the overall destruction of his work aside, the overall reception that much of his work received was initially poor, and to this day there is a barrier of misinformation and false beliefs that still has to be knocked down to understand Yamasaki and his new-formalist designs. While he initially received glowing praise for his earlier projects (including Pruitt-Igoe), much of his later work was snubbed or maligned entirely by critics and locals. The blame that Yamasaki received for Pruitt-Igoe, and how he became the poster-boy for the failure of the modernist movement, certainly left an unremovable stain on his tapestry of work. Around the time that it fell, many documentaries and reports were made upon Pruitt-Igoe and the “death” of the modernist dream, the end of the utopia that architects such as Yamasaki had been striving for. Oscar Newman’s

“Defensible Space” was broadcast in 1974; it’s a fascinating glimpse into the beliefs of the time, and the narrative that urban planners and architectural critics were trying to paint about modernist buildings, and the apparent psychological effects they could have on the occupants inside. Interestingly the documentary falsely claims that Pruitt-Igoe’s final design was “prize-winning”, and Newman himself states the Yamasaki “got every single award….” This isn’t true. Neither Pruitt-Igoe, nor its architect received any awards, yet Newman and others continuously cite it as a sheer sign of the failure of modernism, a naïve architectural ideal that was built for function and purpose, without considering the humanitarian elements of security and homeliness. Newman claimed in his documentary that architects like Yamasaki were “not concerned with the needs of people (....) They answer their own needs. They’re more concerned with the design of projects and buildings with producing something that’s going to win them a design award ...” This narrative that was pushed discarded all external or behind-the-scenes factors, and instead encouraged “less knowledgeable or attentive readers to naively attribute the project’s lack of success solely to Yamasaki’s design.” Only until recently has this narrative been challenged, and it’s safe to assume that those who do know about what really caused Pruitt-Igoe to fail, are few and far between as far as the general public goes.

|

Death of a dream; Pruitt-Igoe was declared to be the end of

Modernism. |

I feel it’s genuinely tragic that such a prominent architect with good intentions, ended up declining so spectacularly in both the public eye and architectural community. It’s brutally unfair that his two most publicized and famous works were both destroyed, taking human lives with them in various ways, but the misinformation and hostility that surrounded him and his buildings even before 9/11 was mostly very misguided. Many people believe that the World Trade Center was misunderstood when it was first built, and that it did indeed have a subtle beauty in its design (something which I agree with wholeheartedly). However I feel it’s safe to say that Yamasaki and his philosophy towards architecture as a whole was also misinterpreted due to external factors, or even misunderstood entirely. Many panned his work as “dainty” or “prissy”, but it was these designs that gave his work a unique personality and voice, especially in the buildings he designed that weren’t high-rises. As times and tastes changed, Yamasaki stuck with his new-formalist style, which alienated observers and made his work appear “frivolous, naïve, and disconnected.” Although his work became less humanist and more functionalist, his uses of slitted windows and gothic arches became common traits of his buildings. His focus on apparently delicate structures ironically gave both his biggest high-rises a sense of security and impenetrable might, and his smallest low-rise structures a sleek (yet welcoming) appearance ripped straight from a pulp sci-fi magazine. Architectural critic Ada Huxtable advised Yamasaki that “the most beautiful skyscrapers are not only big, they are bold ...” However Yamasaki did not believe in this; his formalist and modernist ideals revolved around function and purpose. He believed that architectural designs should arise out of a “valid structural reason, rather than from an impulsive, emotional reason.” Due to this philosophy of his, the Twin Towers may have stuck out of the Manhattan skyline like a sore thumb in the early ‘70s, but the imagery of the two immense skyscrapers standing side by side gave the impression that they were two behemoths created by a god rather than people. Speaking as somebody who was born after they were destroyed, photos of the towers still give me an intense gut reaction, a feeling that they were unmovable as mountains, fixed to the bedrock with unshakeable might. Off the scale. Too large and too strong to have been placed there by the feeble hands of humans. Yamasaki’s designs helped create two skyscrapers that, even to this day, look as though they would survive dozens of plane crashes.

|

There and gone; the Twin Towers fade into low cloud, their lights casting

ghostly apparitions in the mist. |

Minoru Yamasaki may be largely unknown in the public eye, outside of his ill-fated buildings, however the architectural communities that originally scorned his work and viewed him as an outsider, are starting to evaluate and reassess his buildings with the passage of time and knowledge as guidance. Although it’s pretty wrenching to see what became of his work, and how it tainted his legacy as a whole, I hope that someday in the future, people will be more aware of the injustices that he suffered before 9/11 even occurred and can sympathize with what he was going for. Of course, I’ve seen no real recent disrespect or blame placed on Yamasaki for the failings of Pruitt-Igoe, modernism, or the World Trade Center. However, if more are aware of the story of this man and his work, then maybe when his name is mentioned, the imagery of billowing dust clouds and piles of shattered concrete and steel, will be replaced by a vision of a utopia instead. A utopia full of gleaming silver office towers, archways of fiberglass and marble, and “rivers of green” between apartments (both low-rise and high) full of children playing and adults walking dogs or pushing prams. That, I feel, should be his legacy.

THE END

-and-his-bandmates-in-kraftwerk.jpg)